Introduction

Windows are an intrinsic part of our built environment. Not only do they admit light to an interior and permit views to the outside world, they also comprise the public face of a building and help shape how a facade expresses itself

A wander along a typical Irish street can be a feast for the eyes, highlighting the way in which windows are arranged in an elevation, their glazing patterns and detailing, and their opening format – such as sash or casement – all contribute to our collective national architecture that makes us part of who we are and makes our buildings look the way they do. This is especially true of Ireland, where most traditional street architecture and vernacular buildings depend upon basic classical rules of proportion and detailing for their architectural effect, rather than applied decoration that is commonplace in other countries.

This requires understanding and careful management, as if the subtle balance of proportion and detail of historic windows is upset or discarded, the harmony and integrity of our built heritage can be irreplaceably eroded. However, by understanding the historic evolution of window design and technology, and the influences of architectural thinking, it becomes possible to appreciate the joys of Ireland’s window heritage, making every journey along a road or street a stimulating delight for the eyes.

Influences on Window Design

We often take the appearance of our buildings for granted, however all structures are shaped by a number of factors – whether environmental, functional, economic, fashion or others – and this is also true of windows. Until the early years of the twentieth century, most of Ireland’s buildings were governed by rules of classical proportion, borne out of the revival in classical thinking that arrived quite late in Ireland, in the 1600s, following the influence of the Renaissance sweeping across Europe.

This architectural fashion is often thought of in terms of our major public buildings, but its influence was far-reaching, ensuring that for nearly three hundred years most of the buildings of Ireland’s villages, towns and cities, as well as its rural architecture, would conform to basic neo-Palladian principles of design. Symmetrically positioned windows, centrally placed doors, tall rectangular window opes, and elegantly designed window glazing that mirrored the proportions of the building, all became commonplace. This created a remarkably consistent ‘national architecture’ that lasted as late as the 1950s until modernist thinking firmly took hold and altered perceptions about how buildings should look.

Likewise, the availability of technology, such as new developments in glass-making, determined how windows were glazed in certain parts of the country compared with others, while local fondness for a particular type of detail resulted in delightful regional variations within the classical canon of window design. Fashion and functionality also went hand-in-hand, ensuring that the reliable sliding sash was the dominant window type in Ireland for 200 years, with casements only making some headway by the late nineteenth-century as picturesque notions and international influences began to encourage change. These and many other factors helped to shape Ireland’s window heritage and help explain why our windows look the way they do.

This architectural fashion is often thought of in terms of our major public buildings, but its influence was far-reaching, ensuring that for nearly three hundred years most of the buildings of Ireland’s villages, towns and cities, as well as its rural architecture, would conform to basic neo-Palladian principles of design. Symmetrically positioned windows, centrally placed doors, tall rectangular window opes, and elegantly designed window glazing that mirrored the proportions of the building, all became commonplace. This created a remarkably consistent ‘national architecture’ that lasted as late as the 1950s until modernist thinking firmly took hold and altered perceptions about how buildings should look.

Likewise, the availability of technology, such as new developments in glass-making, determined how windows were glazed in certain parts of the country compared with others, while local fondness for a particular type of detail resulted in delightful regional variations within the classical canon of window design. Fashion and functionality also went hand-in-hand, ensuring that the reliable sliding sash was the dominant window type in Ireland for 200 years, with casements only making some headway by the late nineteenth-century as picturesque notions and international influences began to encourage change. These and many other factors helped to shape Ireland’s window heritage and help explain why our windows look the way they do.

Early Windows

A large glazed opening in a wall allowing light to an interior is a relatively modern innovation in Ireland, as limited glass-making technology and the practical need for defence militated against such extravagance until the seventeenth century. Before this time, windows in castles and defensive buildings were small and randomly placed, typically serving a security function in the form of arrow loops, or as narrow slits lighting stairwells and closets – many of which were not glazed at all.

Larger mullioned windows were deployed sparingly in reception rooms and the great halls of castles and tower houses, but in most cases only small diamond-shaped panes of glass known as ‘quarries’ were used. These were hosted within leaded metal or timber frames, often fixed in position to ensure the wind did not catch open casements, and were unlikely to be very transparent. The country seat of the Ormonds at Carrick-on-Suir Castle was so flamboyant in its display of large glazed windows in the 1560s that it was likely to have set a new trend in fortified house design.

By the 1600s, a greater number of merchant and noble houses were being built in towns and cities, some of which were still timber-caged and others increasingly built of brick and masonry. These dwellings regularly displayed ambitious arrays of large windows, indicating not only the confidence of their builders but also the wealth and prestige of their occupants. However, technology still limited the format of glazing to quarry panes or small square panes, with the window openings divided by timber or masonry mullions.

Much of the glass used at this time was originally imported from countries such as France and the modern area of Belgium, however by the early 1600s there was a number of glassmakers based in Ireland producing for the local market, many of whom had originally come from the Continent and brought their trade with them. Fashionable new houses being built on Dublin’s Aungier Street and St. Stephen’s Green from the 1660s onwards are likely to have featured such glazed windows, with a drawing of a house on College Green from as late as the 1680s indicating that quarried panes and mullions were still in use at this time. In smaller houses, rural cottages and cabins, it is unlikely that glazing featured at all until the eighteenth century, with translucent fabric or skins used to keep out the wind and rain while admitting some light. Glass was the reserve of the privileged few.

Arrival of the Sash Window

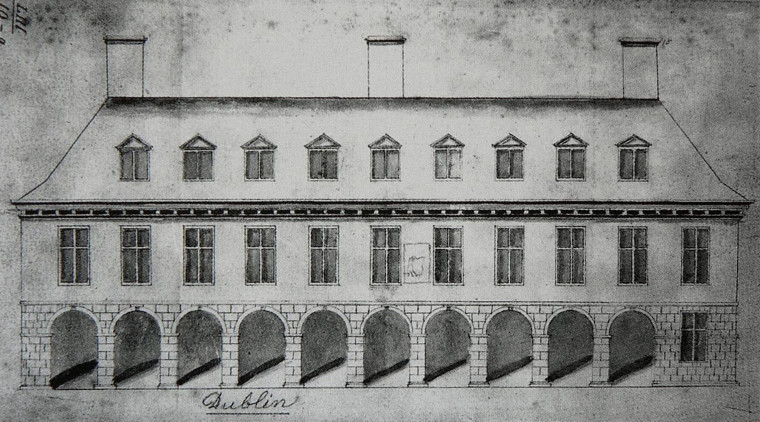

Window manufacturing, and by association the very appearance of Ireland’s buildings, was revolutionised with the introduction of sliding sash technology. This coincided with a growing interest in classical architecture, spurred on by public building projects such as Dublin’s Royal Hospital at Kilmainham and the gradual reconstruction of Dublin Castle.

Arrival of the Sash Window

Window manufacturing, and by association the very appearance of Ireland’s buildings, was revolutionised with the introduction of sliding sash technology. This coincided with a growing interest in classical architecture, spurred on by public building projects such as Dublin’s Royal Hospital at Kilmainham and the gradual reconstruction of Dublin Castle.

Windows became taller and narrower in the classical manner, though in some cases, such as the new State Apartments in Dublin Castle or Lord Clancarty’s mansion on College Green, both built in the 1680s, mullions and transoms continued to be used. The reorienting of the window ope from horizontal or square to a vertical rectangle created the ideal shape to accommodate the sliding sash format, with Kilkenny Castle being one of the first structures in Ireland to utilise them in 1680. It is unclear exactly where the sash or ‘case’ window first originated, but it is likely that the court of King Charles II adopted the format upon its return from France following the Restoration – refining and developing the French model in England and thus encouraging its universal adoption amongst people of fashion. In any event, it would appear that Ireland was equally keen to adopt the style, with widespread use in all forms of building documented as early as the 1730s.

Early forms of sash window looked quite different to the majority that survive today. Initially, some sashes were probably not counterbalanced with weights, but instead pegged, with timber or metal dowels manually inserted beneath a lifted sash to keep it open, while in other cases one of the two sashes was likely fixed in position.

Glazing bars were also dramatically different in appearance, featuring chunky ovolo-shaped sections of up to two inches’ breadth, often detailed at the joints with a square block. This aesthetic was essentially a continuation of the older mullion and transom format, where vertical and horizontal elements in a window had long been considered an intrinsic part of architectural expression. This thinking transferred to the new sash window, where the muscular, densely gridded pattern of thick glazing bars was considered to lend strong articulation to the facade of a building, especially when painted white or a stone colour, causing the grid to visually leap out amongst inky panes of glass.

Early sash windows were placed flush with the facade with their weight boxes entirely exposed to the outside, causing windows to become a very prominent part of buildings, surrounded by a thick frame of timber in a wall of brick or stone.

This fashion continued until 1730, when an Act of Parliament specified that windows in new buildings were to be set back by one brick from the plane of the facade. While this provision appears to have been adhered to, exposed sash boxes continued to be popular until the 1760s, exhibiting a gradual diminution in size over that time. In many rural areas and towns, exposed boxes never really went out of fashion and continued to be made according to the local joiner’s taste.

Refinement of Style

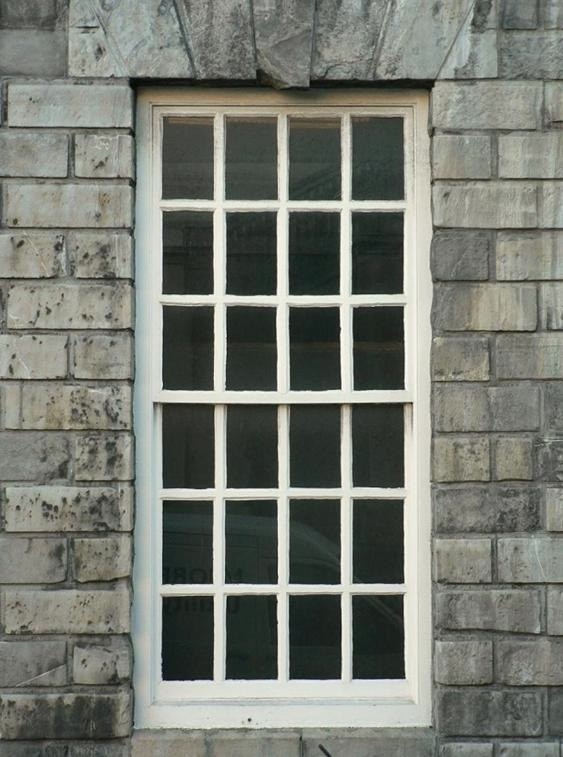

At the eighteenth century progressed, sash window design gradually became more refined as efforts were made to increase the amount of light entering rooms and reduce the ratio of timber to glass, thus improving views to the outside. As a result, the components of the sash frame – the meeting rails, the stiles and the glazing bars – all became thinner and more delicate. A discernible difference can be noted in windows dating from the 1730s, the 1760s and the 1790s respectively, as the search for more light resulted in the emergence of remarkably slender frames by the end of the century.

This was encouraged by a better understanding of classical design, where windows were intended to be read as voids within planar facades, resulting in glazing bars and other members being reduced in size and rendered virtually invisible by the application of a dark paint colour. Small square panes of glass also gave way to taller, rectangular panes that mirrored the proportions of the window ope as a whole. Thus, from architectural dominance at the beginning of the century, window design was transformed into delicate glazed tracery by the turn of 1800.

The interior detailing of windows also evolved during the eighteenth century. Previously, window shutter boxes were squared and straight, dressed with chunky raised and fielded panels and heavy lugged architraves.

As the century progressed, shutter boxes became splayed at the sides to allow more light into the room and to improve oblique angles to the outside – likewise, lugged and shouldered frames gradually disappeared by the late 1770s. By the 1780s, boxes were often splayed to their tops to bounce light onto the ceiling and visually jointed to the shutters with attractive ribbed fan detailing. Windows also became longer, dropped almost to floor level in the most important public rooms. In older houses, the masonry aprons and sills beneath original small windows were often knocked out in order to achieve this effect, replacing old-fashioned sashes with new, slenderer ones in the process.

Regional Variations

The design of sash windows varied in different parts of the country. The standard windows of Dublin were remarkably uniform in the eighteenth century, mostly comprising six-over-six and nine-over-six pane formations, with some exceptions. They were typically square-headed and quite refined in detail, with fashion consciousness ensuring a general consistency in appearance.

In Cork, by contrast, segment-headed windows, where the top sash was slightly curved, were commonplace, as were twelve-over-eight and eight-over-eight glazing patterns, as seen in areas such as Dyke Parade. Segment-headed windows were also a feature of early eighteenth-century buildings and continued in use in some parts of the country after they had gone of fashion in urban centres. In Wexford, a peculiarity of the town was fixing the top row of panes to the window frame, possibly to reduce the weight of a larger upper sash. In the south-west, the English window sill was a common feature in sash windows long after it had died out in the rest of the country.

This took the form of the timber sill underneath the bottom rail projecting out to the front face of the sash box, whereas the Irish sill remained level with the bottom rail – a subtle distinction. This is also a common feature in imported windows, or windows designed by English architects in Ireland, such as Dublin’s Heuston Station and various barracks.

The Taxman Cometh

There are many myths about the taxation of windows and glass which can lead to a misunderstanding of architectural intentions surrounding windows. Unlike in Britain, where it had been in operation since 1696, Ireland was not subject to the notorious Window Tax until 1799, when it was introduced to bolster State coffers during war in Europe. The tax was made progressive through the exclusion of all properties with less than five windows – essentially most cottages and cabins – and thereafter imposed on a stepped scale based on the number of windows in a property, rather than the size of windows. A typical five-windowed house would be liable for 4s 10½d per annum. Only when windows reached a very considerable scale, or were divided by a pier of one foot or more, were they classed as two windows. The tax was abolished in Ireland in 1822.

Therefore, blocking up windows was not a commonplace practice here due to the relatively short duration of the tax’s imposition. The blind opes featured in some Georgian buildings are usually a deliberate device of architectural symmetry to retain balance in a facade, or to generate subtle interest on a gable wall, where windows are not required. Nonetheless, it does appear that the Window Tax did have an impact in one respect – namely the number of windows used in buildings erected in the first decades of the nineteenth century. This is discernible in houses of Dublin’s Fitzwilliam and Mountjoy Squares, where houses built before 1799 are typically of three bays, while those completed in the 1800s and 1810s are almost universally of two bays.

The Window Tax is also likely to have popularised the tripartite Wyatt window, enabling one large window to be used where previously two had been deployed. This became immensely common in the opening years of the nineteenth century, particularly to the rear of houses where Wyatt windows often feature the whole way up bows and flat elevations.

Excise tax on glass was the second form of taxation imposed on window glazing, first introduced in Britain and Ireland in 1746 on all forms of glass and measured by weight. It was revoked in Ireland in 1780 with the aim of promoting the glassmaking industry here, which was achieved with considerable success with the flourishing of glasshouses across the country in ensuing decades. So successful was the measure that concerns were soon raised about the profitability of Irish glassmakers and their competition with British manufacturers. Consequently, a glass excise tax even higher than in Britain was imposed in 1825 on all glass sold in Ireland, with crippling consequences for the glassmaking industry in the country. The tax was finally repealed in 1845 but the industry here never recovered.

Like the Window Tax, the imposition of excise on glass appears to have subtly influenced the design of windows in Ireland through the resulting prohibitive cost of utilising technological advances in glassmaking. Heavily taxing glass by weight appears to account for the slow adoption of heavier improved cylinder and patent plate glass in Ireland during the 1830s and 1840s (discussed later in the glass section), probably causing the continued popularity of the Georgian style gridded sash with cylinder or broad glass well into the nineteenth century.

Glass Types

For centuries, glass was the single most influential factor on the design of windows. The size in which glass sheets could be produced dictated the number, size and even the shape of panes in a window. Similarly, the quality of glass produced by different manufacturing techniques influenced the type of glass used in different buildings, or even parts of the same building.

As a result, the design of historic windows often has a story to tell beyond the mere appearance of the windows and how they relate to their surroundings. For example, the wealth or prestige of a building’s occupants can usually be told by size of the window opes, the type of glass used, and the design complexity of the timber elements, as well as indicating the technological advancements and standards of craftsmanship of a particular period in time. These are important aspects to consider when assessing surviving historic windows.

Early Glass

Until the late seventeenth century, most window glass was made of broad cylinder sheet, also called ‘broad’ or ‘muff’ glass. This was a relatively primitive form of glazing, where a hand-blown cylinder of glass was cut open and flattened out on a table while still hot, often adopting the imperfections of the table surface and the flattening tools used.

This glass was inconsistent in thickness and peppered with flaws, resulting in a demand amongst the privileged few for better quality imported glass from the Continent. Nonetheless, broad glass remained the dominant glazing material until the eighteenth century and was made in Ireland, Britain and the Continent. Even following the emergence of crown glass, broad cylinder sheet appears to have remained popular until the early nineteenth century.

Crown Glass

Crown glass was the king of window glass and dominated glazing in Ireland and Britain for 150 years. Originally developed in the French Normandy city of Rouen in the 1300s, the technology was not exploited in Britain until 1678, where the first maker used a crown as a trademark, hence the adopted name. Records indicate that Ireland immediately followed suit, with crown glass being produced here in at least the first decade of the eighteenth century, with many more manufacturers specialising in the material by mid-century.

Crown glass had a unique appeal due to its clarity, lustre and relative flatness in the best class of the product, and can be identified through the distinctive concentric swirls created during its manufacture.

It was produced by hand-blowing molten glass into a hollow globe on the end of an iron blowpipe, using a horizontal bullion bar to facilitate the shaping. After a process of heating, blowing and reheating, the globe was then transferred to a ‘punty rod’ which was used to spin the flattened globe at increasing velocity in front of an intense ‘flashing’ furnace. This encouraged the globe to expand and finally unfurl in a single motion into a large thin disc of almost perfectly even thickness, typically four to four and a half feet in diameter. The heat of the furnace effectively polished the surface of the glass, giving it a distinctive luminosity and clarity that was impossible to achieve by other means. The centre of the crown disk was pock-marked with the ‘bullseye’ or ‘bullion’ where the punty rod was attached, however even this part was sold as a cheaper form of glass for use in taverns, basements and outbuildings. The crown disk was finally allowed to cool in a kiln under decreasing temperature over the course of twenty-four hours.

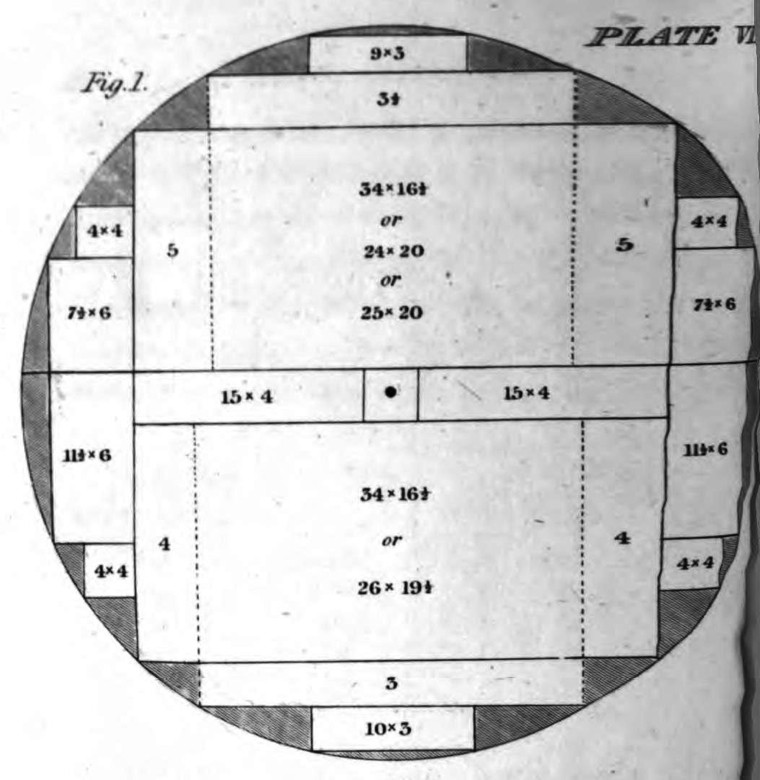

The skills required in using crown glass were not just limited to the manufacturing process, as the cutter’s and glazier’s role was equally as important. Crowns were usually cut in the manufacturer’s warehouse and not on the building site, with the disk first cut in half and then sorted into different qualities commonly known to those in the trade as firsts, seconds, thirds and fourths. Marking up and cutting a crown into standard window pane sizes was a skilled process, as it required a command of mathematics and a keen eye for the qualities of individual crowns and how best to exploit their unique characteristics. Poorer quality crowns were recommended for smaller pane sizes, with high quality crowns reserved for standard or large panes. The key aim was to avoid wastage of valuable glass, with the result that complex diagrams and measurement guides were used to ensure that every square inch of glass in a crown was exploited as a saleable product. Consequently, only a fraction of glass measured from a single crown ended up in the same window, where standard panes may have been cut for use in a house or public building, and the smaller remaining panes used in a church, cottage or industrial premises. Glaziers usually purchased standard pane sizes for an intended job in advance of going to site.

The diagrams (pictured) indicate the extraordinary pane sizes that could be achieved with standard crowns, affording the possibility of pane dimensions up to thirty-six inches long by sixteen and a half inches wide.

Transporting glass was a headache, with glaziers advised to pack glass in timber boxes filled with meadow hay. Small panes were be stacked in dozens before intervening with a layer of hay, with medium panes stacked in half dozens and the largest panes arranged in piles as few as two or three. Care was also to be taken where panes were naturally warped as this could lead to breakage where pressure was applied. The same was advised when glazing a window, as the distinctive ‘belly’ of crown glass caused by the flashing process required carefully managed placement within a window, as noted in this guide from the Crown Glass Cutter and Glazier’s Manual, 1835:

“The convex, or round side of the pane, where such a shape occurs, should be presented to the outside, and the concave or hollow to the inside. The reasons for recommending this disposition of such panes are so obvious that they hardly need be enumerated. It may, however, be stated generally, that, when thus placed, they resist the weather better than if the hollow sides were exposed to it.”

A uniform orientation of glass within all panes was also important, ensuring that each sash or casement had a consistent array of ‘bellies’ catching the light from the same direction.

Improved Cylinder Sheet Glass

This form of glass, often called cylinder sheet, was an improved manufacturing technique for traditional broad or cylinder glass which had been refined on the Continent in the eighteenth century. It was introduced to Britain by the Chance Brothers in 1832 and quickly revolutionised how window glass was produced.

The process involved creating much larger cylinders than before, now measuring up to six feet long, which were allowed to cool before being cut along their length. They were then reheated in a furnace and allowed to unfurl under the extreme heat, creating better quality glass than manually flattened broad glass, with the added benefit of much larger sheets which were typically sold in sizes of 50 inches by 36 inches. For the first time, Georgian grid windows could be affordably replaced with two-over-two and one-over-one pane formations. Nonetheless, the adoption of cylinder sheet in Ireland appears to have been slow due to the punitive excise placed on the weight of glass until 1845, resulting in lighter crown glass retaining a competitive advantage until then and thus the continued popularity of the Georgian grid until at least 1850.

Cylinder sheet can be identified by the evenly warped or battered appearance of panes as they catch the light, often featuring small slender bubbles generated by the cylinder elongating process. The adoption of this new type of glass makes it relatively straightforward to date a building, as two-over-two panes rise exponentially in use in Ireland from the late 1840s onwards, often with cylinder reserved for the reception rooms of large houses and commercial buildings with traditional Georgian grids to the upper floors.

The reordering of the facade of Dublin’s Mansion House in 1851 was one of the first high profile projects to make use of cylinder sheets, with fashionable two-over-two sashes installed on both floors of the principal facade.

From 1860, larger one-over-one cylinder sheet windows become more commonplace, presumably as glass prices decreased and the risk of breaking a single large sheet was less onerous, with two-over-twos then relegated to upper floors and basements. Only by the late 1870s, following three economising advances in manufacturing over the previous decade, did one-over-one panes become commonplace in all windows of most middle class housing and commercial buildings.

Plate Glass – Polished and Patent

The earlier form of this glass, polished plate, was highly prized and expensive due to the quality of the glass used – typically high quality crown or broad glass, or glass cast on a smooth surface – and the labour-intensive process of manually grinding and polishing its surface to produce a rich, smooth finish. Polished plate was usually reserved for mirrors and other high status use, as evidenced in this account relating to the Viceregal Lodge in Dublin’s Phoenix Park from October 1825:

To Francis Johnston Esq.

I enclose herewith […] requisitions which have been received from His Excellency the Lord Lieutenant’s Private Secretary viz.

To have the Glass taken out of the lower part of the Windows in the West Wing of the Vice Regal Lodge and to put in muffed or ground Glass in place thereof.

Estimated at: £14.2.7½

Patent plate glass was initially developed in the 1830s, utilising the concurrent development of cylinder sheet to produce higher quality, large panes of glass by grinding its surface.

Due to its expense, it is likely that patent plate glass did not make much advance on plain cylinder sheet until the 1870s, when Pilkington of England fully mechanised the polishing process and began production on a large scale. Patent plate can usually be identified by the fewer surface imperfections evident in cylinder sheet (due to the grinding and polishing), and by its relatively late introduction to the mass market, c. 1870.

Drawn Glass

This form of glass was developed in the highly competitive era at the turn of 1900, where American, Belgian and English manufacturers competed for domestic and international markets. Drawn glass was one of the fruits of this innovation, involving the drawing of long, continuous ribbons of glass along rollers.

The characteristic feature of drawn glass is the array of faint ribbon-like lines running in parallel across otherwise flawless panes. This glass also made larger sheets affordable for a host of commercial applications, notably shop windows.

Float Glass

Modern float glass is flawless flat glass invented by Pilkington in the 1950s, created through casting molten raw materials over a bath of molten tin. The era of distinctive characteristics in mass-produced glass came to an end.

Glass Colours

Historic glass often features distinctive tonal qualities that developed as a result of impurities in the raw materials. A green tinge is the most common colour, caused by an excessive amount of iron in the fine glass sand.

A pinkish hue is also regularly seen, however this was artificially generated by adding manganese during the glassmaking process to prevent the green tinge developing where sand was known to be iron-rich. If the mix was incorrect, as was often the case, glass could end up with a pink, and in some cases both a pink and a green tinge.

Accommodating Change – Technology and Style

Historic windows were usually made of high quality materials, typically slow-grown, evergreen softwoods imported from Scandinavia and the Baltic countries. This meant that a timber window frame usually outlasted the glass it hosted, both in terms of breakages and technological advances. Therefore, it made sense when larger sheets of glass became available to simply retain the existing frames, cut out old glazing bars and crown glass, and replace them with single sheets of cylinder or plate glass.

This was a commonplace occurrence across the country in the nineteenth century, with the result that windows which to the casual observer appear to be late Victorian can often date to the eighteenth century. This is usually evident in three respects: the filled in sockets for the original glazing bars, the slenderness of the sash frame, and the absence of horns on the corner joints.

As the nineteenth century progressed, the design of new window frames evolved through necessity, as not only was glass technology changing the appearance of windows, it was also affecting their structural integrity. The sheer weight of large cylinder sheet and patent plate glass – which could be up to four times heavier than delicate crown glass – demanded a more robust frame to host it. Consequently, sash members such as stiles, meeting rails and even glazing bars when used in a two-over-two arrangement, became much bulkier and effectively backtracked on the progress that had been made in the eighteenth century in making windows slenderer.

A further key development was the emergence of the ‘horn’ or ‘joggle’ – a decorative projection to the tops and bottoms of meeting rails that facilitated a stronger joint with the stile. Horns are unseen in Ireland until the 1830s, and appear to have been a response to the emergence of cylinder sheet glass in Britain, even though traditional Georgian-style windows dominated here until 1850 and thus were probably unnecessary. Horns from the 1830s to the 1840s were usually primitive, convex shapes, graduating into more decorative concave, ogee and other curvilinear forms thereafter. As a result, it is quite a straightforward task to date windows from this period, however it is always important to take account of regional variations.

By the end of the nineteenth century, casement windows became popular in suburban housing and commercial buildings, usually featuring a tilting top light with stained or leaded glass, and two large casements of clear glass below.

They often feature handsome brass opening mechanisms, catches and handles to the inside.

The Arts and Crafts style further promoted this fashion for casements, encouraging a return to picturesque medieval forms of leaded timber window, while the neoclassical revival in the Edwardian period and later prompted the re-emergence of the Georgian sash window, which is distinguishable from earlier types by the type of modern cylinder glass used and the presence of curvilinear timber horns.

Metal Windows

Windows made from metal have a long history in Ireland, having their origins as far back as the leaded light frames of the late medieval period.

Technological developments during the Industrial Revolution permitted new cast-iron windows to enter the market, however surviving examples from the eighteenth century, such as metal sashes and casements, are rare in Ireland. More commonplace are fixed, multi-pane windows in industrial buildings and churches, where cast-iron frames were favoured for their functional and often picturesque qualities. Further advances by the early Victorian period popularised cast-iron as a glazing structure for glasshouses, facilitated by the production of larger panes of cylinder sheet glass, while the mass erection of artisanal and labourers’ housing later in the nineteenth century created a demand for modular window frames which cast-iron could provide.

The result was the delightful multi-pane windows of housing schemes seen in model estates and developments by the Dublin Artisans Dwellings Company in places such as The Coombe and Harold’s Cross.

The popularisation of the timber casement window in the early 1900s in residential and commercial buildings helped to facilitate the growth in cast-iron and steel windows, as the long-held attachment to the sliding sash format began to wane. The use of metal windows was given an unexpected boost with the rebuilding of O’Connell Street in Dublin and Patrick Street in Cork following the 1916 Rising and the War of Independence.

The reconstruction of these main streets afforded the opportunity to look abroad to the United States and London, where major commercial firms were utilising metal-framing and glazing in new buildings, often in the fashionable stripped style of ‘commercial classicism’. In the reconstructions, major premises such as Clerys and Elverys in Dublin and Grants in Cork exhibited fashionable metal window frames and apron panels, sometimes ambitiously rising two storeys in height.

Elegant bronze windows were also popular, adding a touch of sophistication alongside Portland stone or granite facades.

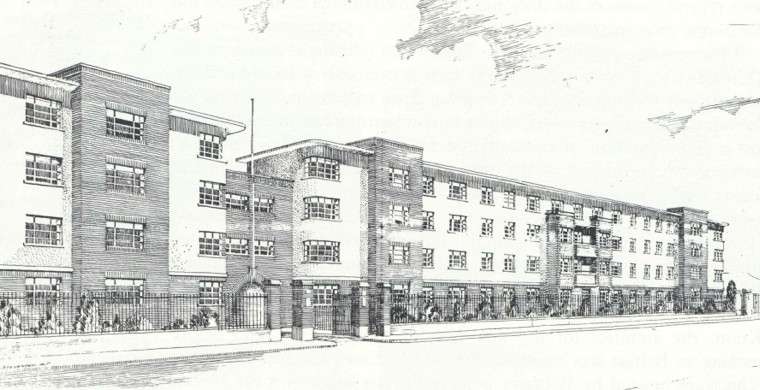

The 1920s and 1930s saw an explosion in the use of metal windows in residential housing, as developers sought to benefit from convenient modular systems that could be rolled out on a large scale and give their houses a modern appearance.

Likewise, new social housing flat complexes constructed by Dublin Corporation in the 1930s to the designs of its housing architect, Herbert Simms, embraced metal windows with gusto, with most of its handsome city centre schemes built in the Amsterdam School style exploiting the modernist lines of metal window frames to complement the clean, stylised lines of their host facades. The campaign of hospital construction in the 1930s to 1950s also made liberal use of metal window frames, with their simple, hygienic aesthetic mirroring the modernist style then in fashion. Only the outbreak of World War II halted the march of metal windows, with timber sashes and casements resurging in popularity during the 1940s on account of metal shortages.

Often metal windows were used to give new houses a conservative, traditional look, with densely paned casements lending a nod to the Arts and Crafts movement, sometimes hosted within chunky timber frames. Indeed, more often than not, metal windows continued traditional glazing patterns, with modernist shapes and lines being reserved for more ambitious International Style commercial buildings and private houses seen in places such as Dublin’s Clontarf and Mount Merrion.

It was only in the 1950s that metal windows commonly adopted simple, clean lines, with suburban houses, factories, offices and commercial premises capitalising on the convenience of mass production that metal windows afforded. The majority of such windows were imported to Ireland from Britain, being manufactured at the enormous plants of Hope, Crittal and others.

It was also at this time that mandatory galvanising was introduced, making steel windows much less susceptible to decay than their forebears and further promoting their use over timber. However, the emergence of aluminium windows in the 1960s, which did not require painting and featured concealed hinges and draught proofing, effectively marked the end of the mass production of steel windows. Timber windows made of cheap, fast grown softwoods also provided competition to more expensive, proprietary steel windows.

The aesthetic of the metal window has been much praised for its striking architectural qualities, and is now gaining a renewed appreciation today for its airy lightness of touch and elegant silhouette.

Due to its inherent strength, steel can achieve slender profiles unattainable in timber, particularly for framing windows and doors. The result is often a strikingly delicate appearance, with sinuous thin members evoking a glamorous appearance in structures as diverse as offices and bay windows of suburban houses. The finer details of steel windows are also a delight to behold, often featuring beautifully crafted hot-rolled latches, extension arms, hinges and catches.

In some cases, multi-pane lights with stippled glass feature along the top of windows, evoking the traditional stained glass of Edwardian top lights, while in rarer cases a striking Art Deco pattern in steel may provide a central feature.

With the benefits of modern thermal and structural upgrading, the beauty and authenticity of historic metal windows can now be preserved while continuing the tradition of technological innovation that first popularised them over a century ago.